Dark matters: the reason your smartphone photos are better than ever

Shooting in the dark

If 2013's going to be remembered for one thing in the smartphone world, it's as the year where cameras got good. Almost any device you'd care to name now has a shooter that takes more-than-decent photos in daylight.

That leaves only one battleground where smartphone cameras don't fare so well – in the dark. On some of the biggest phones of the year, the main boasts haven't been about processing power or even the number of megapixels in the camera; but rather how good they are at taking photos once the sun goes down.

The HTC One, for example, was launched in March with only a 4MP camera, but one with much larger pixels (what HTC calls 'Ultrapixels). The reasoning behind that was clear: larger pixels means less noise, better light-gathering and all-round superior low-light performance.

Nokia, as well, has been focused on low-light performance, with both the Lumia 925 and Lumia 1020 featuring innovations like optical image stabilisation and oversampling to improve the phone's low-light performance.

Even Apple put a wider lens and better flash into its iPhone 5S, innovations that are almost exclusively geared towards taking better photos in the dark.

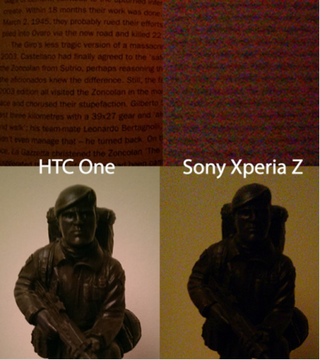

These approaches are a little different from those taken by other manufacturers: Sony is a prime example, with both of its 2013 flagships, the Xperia Z and Xperia Z1, sporting cameras that were big on the megapixel count, but suffered badly compared to the competition once things got dark.

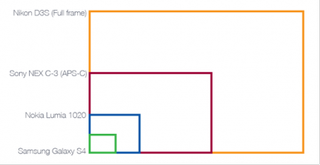

The number one reason why 'proper' cameras – DSLRs – are so much better at taking photos in the dark is that they're a lot bigger. The camera's sensor, the little rectangle that 'sees' the outside world and turns light into electrons, is orders of magnitude larger in a professional full-frame camera like the Nikon D3S, or even a more enthusiast-level mirrorless camera like the Sony NEX C-3.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

That matters because the bigger the sensor, the more light that hits it, and the brighter the picture is. It's like leaving a Post-It and an A3 sheet of paper out in the rain – far more water's going to hit your giant sheet of paper.

Click here to see the full-res image

The end result is that low-light photos, like the one taken above, look great with a large-sensored DSLR, but are a poor-detailed mess on smartphones. In addition to just not being bright enough, there's another problem that plagues smartphone photos taken in the dark: noise.

To compensate for the small sensor size, smartphones often increase the sensitivity of their sensors, a value often referred to as ISO – the higher the ISO setting, the more sensitive the sensor is to light.

However, higher ISOs also generate 'noise', random pixels that light up or change colour, making the photo look grainy and downright horrible. It's not unlike turning your speakers up past where they were meant to – everything turns into a muddy mush.

Bigger (and more expensive) sensors can generally go up to much higher ISO settings without noise, which is one of the reasons DSLRs can shoot much better in low light. Whereas an iPhone or Samsung Galaxy can dial up to around ISO 3200, the very best DSLRs go all the way to 204,800, and even more pedestrian mirrorless cameras hit an ISO around 25,600 with ease.

Click here to see the full-res image

To get around the problems of noise at higher ISO levels, manufacturers – in particular Nokia – have been turning to clever software tricks. Thanks to the 41MP sensor in the Lumia 1020, Nokia are able to employ oversampling, a trick that essentially combines pixels, reducing the overall megapixel count of the camera, but in turn cutting out those rogue pixels that cause noise.