Rumour has it

A photograph is fairly easy to check, but a piece of information can be much more slippery - especially when it's a rumour. People tend to share, repost and retweet rumours without checking whether they're true, and while that's often done with the very best intentions ("OMG just heard the news about X!"), sometimes it's done deliberately to attract attention or to get more website hits.

In some of the most cynical examples, sites will use a headline that's completely contradicted by the actual article, so you'll see "X is dead!" or "Confirmed: iPhone 6 will be made of cheese!" even though the author knows full well that the actual story doesn't back up that claim.

Whether it's Twitter tales of pitchfork-wielding mobs heading for your house or supposedly leaked specs for the next Xbox, the first thing to do is to do the same thing you would with a photo: ask yourself whether it's really plausible, or whether it sounds too good to be true.

Even big news sites can be fooled, as the Daily Mail was when it reported that London rioters had broken into McDonalds and were cooking their own food. They weren't, but by reporting a Twitter rumour as fact, the newspaper legitimised it.

Most of us assume that if a major news source publishes something, it must have fact-checked it first. That isn't always the case, especially during a breaking story. If you think the story sounds plausible and it isn't being reported elsewhere by reliable outlets (reposts and retweets don't count - they're echoes, not corroboration), then the next step is to see if anybody is debunking it.

Sometimes that means finding likely sources of accurate information, such as local council or police Twitter feeds (our child abduction rumour was quickly quashed by our local newspaper and the police, both of which used their official Twitter accounts to spread the news), and sometimes it's as simple as Googling a key detail along with words like 'hoax', 'scam', 'urban myth' or 'debunked', especially if the story has done the rounds before.

Trust no one

"Finding the creators of content is the first crucial step in finding the facts," Nolan says. "At Storyful we've gotten good at locating the first version of videos and pics using a variety of clever search techniques and involving tools such as TinEye, creative use of WHOIS lookups and multiple reverse translations (developed during the Arab Spring) to isolate 'first uploads'."

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

Finding the source isn't always as simple as it sounds though, because stories tend to bounce around the place. The story you saw on your favourite technology blog may have reached it via a chain of other sites, while the person whose post has been retweeted 1,000 times may in turn have been quoting somebody else. If you can't find an original source, take the information you've read with a hefty pinch of salt.

Let's say you manage to find the source of the information. Can you trust that person? Sources tend to fall into two categories: websites and social media accounts. If you're not sure whether they're legitimate, there are several ways to check the reliability of each.

You can check the validity of a website in a number of ways. The first thing to look at is the kind of domain it is using. An official police site, for example, will have a .police domain name, while a UK government site will have a .gov.uk suffix.

Domains anybody can buy, such as .co.uk or .org, are no guarantee of reliability, although you can run a Whois search to see who owns the domain name. That isn't foolproof though, as many domains are purchased through domain resellers, and it's the reseller whose name appears in the Whois.

Remember, too, that reputable sites can be hacked. Does the information you're reading fit with the style of the site's other content? Is it formatted the same way? Does it use the same language? A quick peek at the site in the Wayback Machine enables you to travel back in time to get a feel for a site's content.

The next step is to assess the kind of site you're looking at. Is it an authority in the kind of information you're trying to verify, or is it a cut-and-paste blog that'll publish anything to get some more hits? Is the leaked product information you're reading the result of conversations with a well-placed source, or is it just a collection of wild guesses and wish lists from a financial analyst? Has the site made similar claims in the past, and if it did, did it get anything right?

Watch out, too, for content that's been created by think tanks and lobbyists. Some organisations, such as the US Heartland Institute or the UK's Taxpayers' Alliance, are often the source of news stories that are widely reposted online or brought up in heated message board arguments, but they're not independent; they have specific agendas they're trying to promote.

For example, the Heartland Institute wants everyone to stop worrying about climate change, while the Taxpayers' Alliance is firmly against what it sees as excessive taxation and government waste. That doesn't necessarily mean that the information they provide is worthless, but it certainly isn't unbiased.

Healthy scepticism

It's particularly important to assess the reliability of a source when the information you're trying to verify is life-changing, such as information about health or financial issues.

Reliable sites won't make lurid claims about cover-ups and conspiracies, secrets 'they' don't want you to know or 'miracle' products. Nor will they try to sell you Wi-Fi-blocking earmuffs, a revelatory ebook The Man tried to ban, a proven system to beat the bookies' odds or the weight-loss secrets of the ancient Egyptians' cats.

Be particularly wary of sites that use newspaper articles as sources of information, as such articles often prize exciting headlines over strict accuracy. Tabloid newspapers in particular have a terrible track record in that department: remember the reports about killer Wi-Fi? Not all health-related misinformation is so obvious.

If you go Googling for the possible side-effects of artificial sweeteners, the effectiveness of certain cancer treatments, the complications that can arise from childhood vaccinations or the effect mobile phone radiation has on developing brains you'll find lots of very persuasive, sensible-looking websites that quote apparently reputable studies and that don't appear to be hysterical or biased. That doesn't mean you can trust them, though.

Have they quoted all of the studies in the field, or just the ones that support a particular worldview? Are they reporting correctly, or drawing inaccurate conclusions? Is the information there to help you, or to encourage you to spend money on some kind of lotion or potion? Are the scientists and other experts they quote people you can trust?

As Dr Robert L Park writes in Seven Warning Signs of Bogus Science, "There is, alas, no scientific claim so preposterous that a scientist cannot be found to vouch for it."

The only way to be sure that any health information you're looking at is accurate is to use sites that are transparent, unbiased and doctor-approved, such as the NHS's own website, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and the US National Library of Medicine. If the site you're looking at isn't one of these, it's a very good idea to follow the British Medical Association's advice and look for the tell-tale signs of dubious health sites - advice that really applies to all kinds of information sources.

When you're assessing an online information source you should be looking to see whether it's updated regularly, whether it gives references and sources for the information it provides, whether it supplies details of any sponsors, whether it appears well-edited or slapdash and sloppy, and whether it's trying to sell something.

Taken individually, those criteria aren't always signs you should run away. For example, the British Medical Journal's Best Health website charges for subscriptions, but its content is accurate and excellent. If several warning signs are present though, you really ought to switch on your nonsense detector.

Friends like these

You can often judge a website by the company it keeps, so have a look at the kind of sites it links to and use Google's advanced settings to see what links to it. For example, if a health site links to or is linked to by lots of dubious woo-mongers ('woo' being myth-debunker Dr Ben Goldacre's term for dubious medical claims), there's a very good chance it's a woo-monger itself.

Judging a source is even easier on social networks, where you can see at a glance which accounts a person's profile is connected to. Follower counts can be telling for people in the public eye: a social networking account for a well-known figure that's struggled to reach double follower figures should set alarm bells ringing.

There are other obvious signs that an account might not be what it claims to be. A Twitter account that only came online yesterday is unlikely to be a reputable source, and an account that says it's the Metropolitan Police but that only follows students and comedians probably isn't the real thing.

Twitter itself can help too: some, but not all, official Twitter accounts are verified, which means a big tick appears next to their name on their Twitter profile. So for example, @johnprescott has the tick and is a genuine account while @darthvader doesn't and isn't.

If you're on Twitter, Nolan recommends using its Lists feature to separate fact from fiction. "Building a Twitter list of trusted sources is a good way to start sifting," he says. "Or better yet, build several topic-specific lists so that when a story breaks, you can turn to the people who you trust on that topic."

Just the facts

Social media is great at spreading misinformation, but it's often even better at correcting it. Earlier this year, students on professor T Mills Kelly's Lying About the Past course created an extraordinarily detailed and convincing mesh of fact and fiction about a serial killer. The plan was to fool users of sites such as Reddit, and when the class tried similar tactics back in 2008 they successfully fooled Wikipedia and infuriated its founder Jimmy Wales.

This year, though, the hoax was rumbled in 26 minutes when Reddit users cried foul.

Take your time

Social news sites are particularly good at rumbling false stories, either by investigating them themselves or by circulating corrections. For example, news circulated in May that Chinese manufacturers were putting back doors in microchips headed for the US military; when Robert David Graham analysed and debunked the reports, his rebuttal quickly became the top story on Hacker News.

It helps that we're becoming a bit more cynical too. "The key people, the influencers within the media, are beginning to realise that being first to something that is wrongly sourced is not being first at all, so they're happier to ask questions of content more and more, rather than to scream for the scoop," Nolan says, noting that: "The life-cycle of a hoax, even a half-decent one, is getting shorter and shorter. Mikhail Gorbachev probably had the shortest death-to-resurrection Twitter timeline in history recently. People are better at asking themselves before hitting 'retweet'."

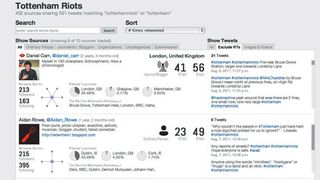

Technology might help too. SRSR, the Seriously Rapid Source Review, is designed to help users filter social media signals from noise during major events. As co-creator Nicholas Diakopoulos explained in a research paper, it is "a high precision eyewitness detector" that filters out retweets, works out where people are, prioritises particular kinds of users (such as local newspaper journalists tweeting from the scene), and looks for 741 different words that eyewitnesses are likely to use.

For example, people who are actually at the scene tend to use phrases like "I'm okay", and people are more likely to mention place names if they're far away from the event than if they're right in the thick of it. If tweets contain particular 'eyewitness words', SRSR then analyses the users' other tweets for more clues, such as media they're sharing or linking to and whether they're tweeting from a mobile device or a desktop PC.

In a test, SRSR was given 12,595 tweets about the London riots to analyse, and the journalists who used it found that it did indeed help them locate genuine tweets from people who were posting from flashpoints.

SRSR is very much a work in progress - for now it only works with a relatively small dictionary and analyses historical data rather than real-time tweets. Diakopoulos says that there are technical challenges in adapting the SRSR algorithms and methods to truly work in real time," but it's packed with potential.

While we wait for technology to create a better lie detector, what should we do when a major news event fills our social media feeds with claims and counterclaims? "Other than be patient? Be prepared," Markham Nolan says. "Social media has brought everyone closer to the news, but the reason journalists still get hired is that there is often some work to do to sift out the news from the noise."

Verifying stories and ensuring that images and videos are what they claim to be is a difficult, painstaking and often time-consuming process, and if you'd rather not do it yourself then perhaps it's best to wait until somebody else verifies the story before sharing it with everyone you've ever spoken to.

If nothing else, that means you won't end up feeling daft if the story is debunked shortly afterwards. As Nolan says: "Not everything that is shared on Twitter stands up factually. Apply common sense, and think before you tweet."

- 1

- 2

Current page: How to spot rumours and identify story sources

Prev Page How to spot hoaxes on Twitter and Facebook