Human tongue turned into computer

And teeth to be its keyboard

Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology are looking into ways to convert the humble tongue into an elaborate computer control system.

The eventual plan, using "Tongue Drive" technology currently under development in the university labs, is to turn the whole mouth into a self-contained computer system, with the tongue effectively acting as a joystick, interacting with sensors placed around the mouth, and even eventually using the teeth as a virtual keyboard.

"You could have full control over your environment by just being able to move your tongue," said Maysam Ghovanloo, a Georgia Tech assistant professor who leads the research team.

Tactile tongue tech

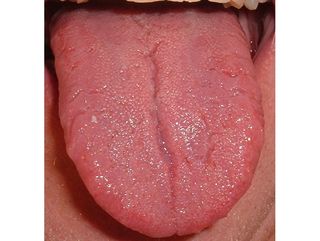

The benefits for people disabled below the neck is potentially significant, as the tongue is often completely unaffected by physical accidents – being attached to the brain and not the spinal chord. Added to that, the tongue is tactile, flexible and doesn't require much energy to use for long periods.

"This could give you an almost infinite number of switches and options for communication," said Mike Jones, vice president of research and technology at Atlanta rehabilitation hospital the Shepherd Center. "It's easy, and somebody could learn an entirely different language."

Mouth magnets

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

Though a Paolo Alto-based company has already come up with its own tongue-based electronic control device – in the form of a nine-button keypad placed on the roof of the mouth – Ghovanloo's solution focuses on a virtual keyboard idea.

The movement of a three millimetre-wide magnet, placed under the tip of the tongue, is tracked by sensors on the side of the cheeks. These signals are converted into movement commands via a piece of (currently rather bulky) headgear.

Ghovanloo said he hoped that one day he would add more commands that turn the teeth into keyboards and cheeks into computer consoles, giving the example, "Left-up could be turning lights on, right-down could be turning off the TV."

However, even at this early test stage, in which a wheelchair-bound volunteer can be seen whizzing around a courtyard, Ghovanloo's work has attracted a $120,000 grant from the National Science Foundation and $150,000 from the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation.

Most Popular