Who'll be first to Mars?

A new space race is kicking off

As the 21st century dawned, more space agencies started getting excited about Mars. In 2001, the European Space Agency (ESA) proposed the Aurora Programme – a long-term vision for the exploration of the solar system. It began with robotic exploration, followed by simulations on Earth and eventually a manned mission in 2033.

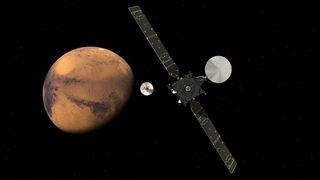

Disagreements among the largest contributors to the ESA's budget have, however, set back that timetable substantially. Missions featuring robotic explorers have successfully launched in the last decade, such as 2016's ExoMars, and these are likely to continue over the next decade.

But it's an open question whether the European Space Agency will develop its own human spaceflight missions in the future, or merely follow behind its international competitors, partnering on specific missions and sharing knowledge without taking a leading role.

To date, many of those partnerships have been with ROSCOSMOS – the Russian space agency. While a number of Mars mission concepts have been proposed by Russian scientists, and some research has been done on the psychological effects of isolation on a long space mission (most notably the Mars 500 study), the country has mostly stayed out of the race to Mars and concentrated on low-Earth orbit instead.

Asian entrants

That has left something of a vacuum, which newer space agencies like China's National Space Administration (CNSA) and India's Space Research Organisation (ISRO) have jumped to fill. Japan's Aerospace Exploration Agency – JAXA, if you're wondering – is taking a more low-key approach, sending robots towards Venus and Mercury, and the occasional astronaut to the International Space Station.

To date, China has seemed more focused on lunar rather than Martian exploration, but that's beginning to change. The country partnered with Europe and Russia on the Mars 500 study, and launched the Yinghuo-1 Mars probe in 2011 which, unfortunately, failed to make it out of the Earth's orbit.

But in early 2016, CNSA announced the 2020 Chinese Mars Mission – a plan to put an orbiter, lander and rover on Mars, delivered on a Chinese Long March 5 rocket. It's planned to be a demonstration mission for the technology necessary for a robotic sample return mission in the 2030s.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

On the manned side of things, China has sent five crews into space since 2003 and has a space station in orbit, but – perhaps recognizing that the country has a lot of catching up to do – has no plans to send humans beyond the Moon yet. That said, don't count China out – it's got the resources, the cash, the technology, and the desire to prove themselves to a watching world.

Another new entrant worth watching is India. ISRO launched a Mars mission, Mangalyaan, in 2013 and successfully entered the orbit of the Red Planet in 2014, making it the first country to succeed on its first attempt to send a probe to Mars, and only the fourth space agency to do so at all.

Like Russia, ISRO's current focus is chiefly on low-Earth orbit, and on launching satellites for other countries (which it's getting very good at), but Mangalyaan 2 is planned for the coming years, while an orbital vehicle that could carry humans into space is under development. Its first launch is due in 2024, and the country's future appetite for manned space missions will no doubt be heavily influenced by the results.

Don't forget Nasa

Then, of course, there's international space flight's biggest player: Nasa. In 2004, US President George W. Bush announced a manned space exploration programme, titled the Vision for Space Exploration. Released in the wake of the Columbia Space Shuttle disaster, its express goal was to "inspire, innovate and discover" public enthusiasm for space policy.

It shifted Nasa's focus away from the space science missions it had been concentrating on (like the Hubble Space Telescope) and back towards exploration, with the ultimate objective of a manned mission landing humans on Mars in the 2030s.

When Barack Obama ascended to the presidency in 2009, he came with his own set of priorities, set out in a 2010 policy speech at the Kennedy Space Centre. His proposals increased Nasa funding, signed off on the development of a new heavy-lift rocket, and predicted a crewed orbital Mars mission by the mid-2030s. However, it also scrapped the behind-schedule Constellation Program, which was the United States' foremost plan to get humans back to the Moon and eventually to Mars.

That 2010 speech was a major turning point for Nasa, and saw the beginning of a shift towards relying on commercially-operated launch vehicles, rather than its own rockets, to put its equipment into space. Mere weeks later, SpaceX successfully launched its Falcon 9 rocket for the first time, heralding a totally new era of spaceflight.

Current page: Into the present day

Prev Page The dream, and the obstacles Next Page Commercial interests