The evolution of virtual worlds

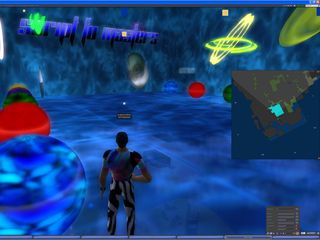

Is this where you'll be spending your time in the future?

Stitching Facebook and MySpace into a 3D environment might not seem like the most exciting project in the history of gaming, but a handful of intrepid gaming companies are wondering if social gaming is going to be the next huge, very profitable thing.

The logic is simple – not everyone enjoys blowing up friends and enemies when they go online, or obsessively assembling a vast arsenal of ultra-weapons and superhuman skills. While World of Warcraft and its medieval and science fiction beat-'em-up and shoot-'em-up siblings have questing and wizarding locked down, the popularity and momentum of social networking suggests that there's serious money to be made from friends and fans. But is this really gaming? And does it matter?

Pride of place in the pantheon of chat-'em-ups goes to Second Life. Whereas most games demand smooth and fast performance, Second Life goes against tradition by offering gamers an experience that's laggy, awkward and slow.

Your fellow players' avatars twitch and jerk around in virtual space like cyber-puppets on springs. When you log in – or res, in game jargon – it can take up to 10 minutes for your surroundings to res around you. Until then, you can find yourself missing essential walls and floors, standing in a void, bumping into nothingness when you try to move and unable to do much at all.

With high-end bandwidth and a top spec PC some of these issues are reduced, but no one would ever accuse Second Life of being excessively polished. The political instincts of Linden Labs, Second Life's creators, are similarly awkward, with regular drama over policy changes and peculiar changes of direction.

It doesn't help that both its client and server software are notoriously bug-ridden and crash prone. Some users can't stay logged in for more than an hour without a crash and the server database regularly ignores transactions – none of which inspires confidence.

User loyalty is even more remarkable considering how expensive Second Life can be. The cheapest entry-level annual subscription costs an eye-watering $72. But you can't do much in the game without buying land. Doing so carries a one-off cost of ownership – fees are variable – as well as a monthly payment for 'tier', or land tax.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

A small patch of 1/128th of a sim costs $5 a month in tier and basic land prices can be astronomical. If you want an entire region or island, expect to pay $1000 up front and a blistering $295 per month in tier. And yet, Second Life remains very popular.

While the total number of registered players is in the millions, only around 100,000 are active. But 100,000 is still an impressively high number for a game that doesn't allow much gaming. Although there are combat areas and a healthy trade in virtual weapons, laggy responses and random res times make Second Life a less than ideal place to engage in online sparring.

Nevertheless, a number of online entrepreneurs have done surprisingly well for themselves selling combat systems and clothes, and by offering other associated services such as bars and chat spaces for after-combat socialising.

While Second Life is a bad platform with conventional gaming, it's popular for people hoping to establish virtual friendships and relationships. There's no lack of people to meet and no shortage of places to meet them. And because avatars and locations are almost infinitely customisable through a combination of scripting language and simplified 3D design and texturing, it's possible to live out a fantasy – whatever that might be – much more easily than in real life.

Newcomers to the field

Newcomers Kaneva and Multiverse have been quick to jump on this idea and have made it their focus. Kaneva is more of a shop-'em-up – you can socialise, you can buy things and you can work for money to make it easier to socialise and buy things. There isn't a lot else to do and, although you can put money into the game to buy virtual items, you can't build and sell new virtual items in order to make money.

If your horizons are broader – or if you're an antisocial billy-no-mates – you may be less than thrilled by the experience. But it's a relatively kid-safe environment and is ideally suited to popular and not so popular teens looking for a wider circle of friends.

Multiverse, meanwhile, is still in beta and offers an even more slimmed down experience of virtual loft living, giving you a wall of friends you can fill up and visit. In its current Multiverse Places form it's more of a virtual chat room than a game space. But it already includes direct links to Facebook, so you can meet your real life friends in a virtual space.

In the longer term, it's pitching itself as a meta-platform for further gaming development – which means that some time in the future you'll be equally able to blow up your real life friends with the usual impressive variety of super-weapons. Or you can buy them lunch. It's up to you.

At the other extreme, Mindark, maker of Entropia Universe, is pitching its alternative meta-platform as a possible business opportunity for lazy or impatient game developers who don't want to develop a 3D engine from scratch.

EU's Calypso game planet is now up and running and gives players a fairly conventional science fiction gaming experience, with mining, monster hunting and collaborative questing to pass the time. The interesting part is that in-game profits can be converted into real cash at a fixed exchange rate of 10:1 with US dollars. It's not an easy way to make money, but once you're skilled and past the noob stage, you may be able to make a respectable £50 a week from your persistent gaming addiction.