What's in store: The tech that will transform memory and storage

From heating to helium and the power of HBM

Spin on this

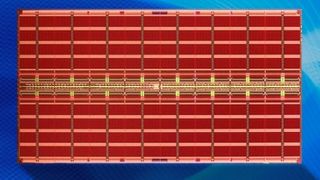

Spintronics is a new, ahem, spin on data transfer. As electrons spin they generate tiny magnetic fields, and those fields can be used to transfer data. That data transfer requires much less energy than traditional electronic circuitry, it can be used in cheap materials such as copper and aluminium, and it's non-volatile, so it retains data when there's no energy source.

Spintronic magnetic RAM – MRAM – already exists. One manufacturer, Everspin, markets MRAM chips for automotive and aeronautical applications, which benefit from MRAM's exceptional resistance to heat and other stresses. It's ideal for flash storage such as SD cards and SSDs, and while it's a little slower than conventional DRAM it's much smaller and more energy efficient. Those benefits mean it can also be used as processor cache memory, which is something Intel, Qualcomm, Samsung and Toshiba are all experimenting with.

Life's a gas

Don't write off the humble hard disk just yet, though. Earlier this year Seagate unveiled a 10TB helium-filled hard drive, following in the footsteps of Western Digital subsidiary HGST. Helium is considerably less dense than normal air, so using it inside drives reduces drag and other forces. That means manufacturers can use thinner platters and pack more platters into the same space. According to Seagate, the mean time between failures (MTBF) of helium drives is 2.5 million hours, compared to 2 million for non-helium enterprise drives.

For all its joys, helium doesn't make hard disk platters store any more information. For that, we need to consider technologies such as heat-assisted magnetic recording, or HAMR for short. HAMR adds a laser to the familiar hard disk design, heating up the platter to cram much more data into the same space. TDK promised to ship HAMR drives in 2016, but the timescale appears to have slipped and HAMR drives aren't expected to turn up much before 2018.

HAMR has a rival: SMR, or shingled magnetic recording. Once again SMR promises more dense data storage on hard disk platters, but it accomplishes this in a different way. Think of the shingles you see on a roof. SMR does much the same with data, creating tracks that overlap part of the previously written track, and Seagate has been shipping drives that use the technology for the last three years.

It works by exploiting the difference between a hard disk's read and write heads: read heads are narrower than write heads, so the overlapping doesn't prevent the reader from getting the full information. Because it's very similar to existing hard disk technology the costs of making it are relatively low, and it enables firms such as Seagate to increase storage densities by around 25%. That makes it a useful step forward while we wait for technologies such as HAMR.

This article is part of TechRadar's Silicon Week. The world inside of our machines is changing more rapidly than ever, so we're looking to explore everything CPUs, GPUs and all other forms of the most precious metal in computing.

Are you a pro? Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

- Also check out: 10 CPUs that changed computing

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall (Twitter) has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than a dozen books. Her memoir, Carrie Kills A Man, is on sale now. She is the singer in Glaswegian rock band HAVR.

WD launches enormous 4TB SD card for creative pros — smashes world record for largest removable memory card to smithereens at twice the capacity of biggest microSD cards

An incredible $100 billion bet to get rid of Nvidia dependence — tech experts reckon Microsoft will build a million-server strong data center that will primarily use critical inhouse components

Most Popular