How computers have revolutionised our cars

Meet the computer models making cars more efficient and building factories

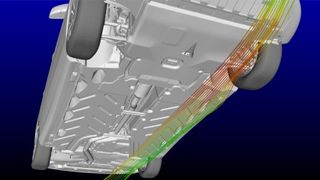

Höfer says there is a magnitude of data available to designers beyond what would be possible in a traditional wind tunnel. The idea is to weed out variables on the computer, and then to verify the virtual testing with a physical prototype, to be more efficient.

"In the wind tunnel we just have the smoke probe and wool tuft test to visualise airflow, which makes it quite discrete," he says. "By using the CFD data intensively, we can analyse and optimise every single streamline, which also helps us in the wind tunnel testing to be more efficient."

The result is that designers can correlate a drag coefficient value directly to mileage. For example, on the specific Mercedes CLA 180 Blue Efficiency edition, Mercedes knows that a 40-count (0.040) value correlates to an increase in 0.4 miles per gallon.

Ford models fuel efficiency in the C-MAX Energi

Computer modelling to determine MPG has evolved recently. In the past, there might have been a model of the combustion system itself, plus the transmission, the battery and related components. Another model might analyse the climate control settings and aerodynamics. Each model lived separately - engine models would maximise efficiency, for example.

Computing power has advanced to enable increased fidelity. One model is still not used to predict total results, but the models are correlated to arrive at an MPG rating.

Dr Mazen Hammoud, the chief engineer of powertrain electrification at Ford, says the company tries to predict the average user at various speeds. On a plug-in, the model has to account for the charge habits of the user - how often they charge up and for how long. Ford models a user who might charge only at the shops each day versus charging only at night.

"Modelling at the vehicle level - underhood temperature and aerodynamics - the interactions between different systems in different driving conditions are subject to assumptions in the model. At 60mph the aero drag is different from at 80mph, for example." he says.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

Another variable has to do with the warm-up process in the car. This is where models get complicated: a driver might be taking several short trips in one day versus another who starts the car once, drives to work, and then drives home later in the day. Warm-up involves lubrication for moving components, the transmission, engine and climate controls. All of the components require energy, not just the direct power to propel the vehicle.

"All energy used comes from the fuel or from the power utility," he says. "This even includes using the heated seats or adjusting the seats. We try to re-generate energy, but to start with, all energy comes from these two sources. All energy you use can reduce mileage."

The Ford C-MAX Energi is rated at 41MPG on the highway, but 100MPG in combined electric and fuel power. The fully charged engine can run as fast as 85mph and can go 21 miles on pure electric power. The driver can also select a hold mode for EV that enables you use it later - say, when you will be driving in the city at lower speeds and want to take advantage of that power source.

"What we have the most data on is what we have in a lab," he says. "It is the most controlled environment. Noise factors such as wind and warm-up have not normally been accounted for in models. As we learn more about plug-ins and how they are used, we are working on developing more models but we are not there yet. We will correlate these findings to the actual driving and experimental data. Unless it is correlated, it is useless."

Ultimately, the models will look at all values inside the car - from the heated seats to the transmission temperature - and generate one number. For now, the data helps create an average that is predicated on real-world testing to verify the lab findings.

John Brandon has covered gadgets and cars for the past 12 years having published over 12,000 articles and tested nearly 8,000 products. He's nothing if not prolific. Before starting his writing career, he led an Information Design practice at a large consumer electronics retailer in the US. His hobbies include deep sea exploration, complaining about the weather, and engineering a vast multiverse conspiracy.

Most Popular